Regular Employment and its Exceptions under the Law

According to the Supreme Court (SC) in the case of Universal Robina Sugar Milling Corporation vs. Acibo (G.R. No. 186439, January 15, 2014) Article 295 of the Labor Code provides for three kinds of employment arrangements, namely: regular, project/seasonal and casual.

According to the Supreme Court (SC) in the case of Universal Robina Sugar Milling Corporation vs. Acibo (G.R. No. 186439, January 15, 2014) Article 295 of the Labor Code provides for three kinds of employment arrangements, namely: regular, project/seasonal and casual.

Regular employment refers to that arrangement whereby the employee has been engaged to perform activities which are usually necessary or desirable in the usual business or trade of the employer. Under the definition, the primary standard that determines regular employment is the reasonable connection between the particular activity performed by the employee and the usual business or trade of the employer.

The emphasis is on the necessity or desirability of the employee’s activity. Thus, when the employee performs activities considered necessary and desirable to the overall business scheme of the employer, the law regards the employee as regular.

By way of an exception, paragraph 2, Article 295 of the Labor Code also considers regular a casual employment arrangement when the casual employee’s engagement has lasted for at least one year, regardless of the engagement’s continuity. The controlling test in this arrangement is the length of time during which the employee is engaged.

A project employment, on the other hand, contemplates on arrangement whereby the employment has been fixed for a specific project or undertaking whose completion or termination has been determined at the time of the engagement of the employee.

Under Art. 295 of the Labor Code, two requirements, therefore, clearly need to be satisfied to remove the engagement from the presumption of regularity of employment, namely: (1) designation of a specific project or undertaking for which the employee is hired; and (2) clear determination of the completion or termination of the project at the time of the employee’s engagement.

Per SC in Universal Robina case, the services of the project employees are legally and automatically terminated upon the end or completion of the project as the employee’s services are coterminous with the project.

Unlike in a regular employment under Article 295 of the Labor Code, however, the length of time of the asserted “project” employee’s engagement is not controlling as the employment may, in fact, last for more than a year, depending on the needs or circumstances of the project. Nevertheless, this length of time (or the continuous rehiring of the employee even after the cessation of the project) may serve as a badge of regular employment when the activities performed by the purported “project” employee are necessary and indispensable to the usual business or trade of the employer.

In this latter case, the law will regard the arrangement as regular employment.

Seasonal employment operates much in the same way as project employment, albeit it involves work or service that is seasonal in nature or lasting for the duration of the season. (Maraguinot, Jr. v. NLRC, 348 Phil. 580, 600-601 (1998).)

As with project employment, although the seasonal employment arrangement involves work that is seasonal or periodic in nature, the employment itself is not automatically considered seasonal so as to prevent the employee from attaining regular status.

To exclude the asserted “seasonal” employee from those classified as regular employees, the employer must show that: (1) the employee must be performing work or services that are seasonal in nature; and (2) he had been employed for the duration of the season. (Hacienda Bino/Hortencia Starke, Inc. v. Cuenca, 496 Phil. 198, 209 (2005)

Hence, when the “seasonal” workers are continuously and repeatedly hired to perform the same tasks or activities for several seasons or even after the cessation of the season, this length of time may likewise serve as badge of regular employment. In fact, even though denominated as “seasonal workers,” if these workers are called to work from time to time and are only temporarily laid off during the off-season, the law does not consider them separated from the service during the off-season period. The law simply considers these seasonal workers on leave until re-employed.

Hence, when the “seasonal” workers are continuously and repeatedly hired to perform the same tasks or activities for several seasons or even after the cessation of the season, this length of time may likewise serve as badge of regular employment. In fact, even though denominated as “seasonal workers,” if these workers are called to work from time to time and are only temporarily laid off during the off-season, the law does not consider them separated from the service during the off-season period. The law simply considers these seasonal workers on leave until re-employed.

Casual employment, the third kind of employment arrangement, refers to any other employment arrangement that does not fall under any of the first two categories, i.e., regular or project/seasonal.

The Labor Code does not mention another employment arrangement – contractual or fixed term employment (or employment for a term) – which, if not for the fixed term, should fall under the category of regular employment in view of the nature of the employee’s engagement, which is to perform an activity usually necessary or desirable in the employer’s business.

In Brent School, Inc. vs. Zamora, the SC recognized and resolved the anomaly created by a narrow and literal interpretation of Article 280 (now 295) of the Labor Code that appears to restrict the employee’s right to freely stipulate with his employer on the duration of his engagement. In this case, the SC upheld the validity of the fixed-term employment agreed upon by the employer and the employee declaring that the restrictive clause in Article 280 should be construed to refer to the substantive evil that the Code itself singled out: agreements entered into precisely to circumvent security of tenure. It should have no application to instances where the fixed period of employment was agreed upon knowingly and voluntarily by the parties absent any circumstances vitiating the employee’s consent, or where the facts satisfactorily show that the employer and the employee dealt with each other on more or less equal terms.

The indispensability or desirability of the activity performed by the employee will not preclude the parties from entering into an otherwise valid fixed term employment agreement; a definite period of employment does not essentially contradict the nature of the employees duties as necessary and desirable to the usual business or trade of the employer.

Nevertheless, “where the circumstances evidently show that the employer imposed the period precisely to preclude the employee from acquiring tenurial security, the law and this Court will not hesitate to strike down or disregard the period as contrary to public policy, morals, etc.” In such a case, the SC pronounced that the general restrictive rule under Article 295 of the Labor Code will apply and the employee shall be deemed regular.

Clearly, therefore, the nature of the employment does not depend solely on the will or word of the employer or on the procedure for hiring and the manner of designating the employee. Rather, the nature of the employment depends on the nature of the activities to be performed by the employee, considering the nature of the employer’s business, the duration and scope to be done, and, in some cases, even the length of time of the performance and its continued existence.

The following are sample probationary employment contracts which can help HR practitioners, business owners, and managers craft with ease:

Get a complete package of probationary employment documents from employment contract, evaluation criteria, notices, etc. through the Super 5 Packet.

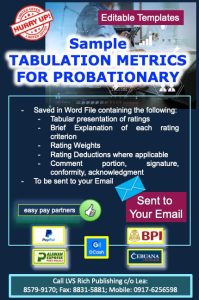

See also the Probationary Tabulation Metrics.